Going forward with boldness

A fox visitation, a book by Terry Tempest Williams, and the role of uncertainty in our lives

Welcome! You’re at Mother E, a monthly newsletter devoted to exploring our kinship with other species in a climate-changing world.

You can also view this post on the Mother E website if it doesn’t display well in your email. And if you missed last month’s post, it’s here: Water harvesters and Imagineers— jobs for the 21st century

This month is the three year anniversary of publishing Mother E! As I start the fourth year of this work, I’m reflecting on how best to carry this forward. I also want to thank YOU for reading, offering support, and generous feedback! You can always reach me at MotherE@Substack.com or by responding to your Mother E email like this post.

Robin A.

AS I WRITE THIS, THE RAIN HAS BEEN FALLING FOR MANY HOURS, blurring the view out the window. When I step outside, the sound of moving water is louder and more varied. There’s the flat tap of water hitting the roof, the bursts of drops blown against the window, and the gurgling rush of a small drainage creek.

Further away, the thunderous crash of storm-swollen ocean waves pounds the shore. Water is playing a symphony today, complete with crashing cymbals.

Where do the animals go during these long hours of wind and pouring rain? I see no birds about. They must take shelter in trees or under bushes. Are they hunched against a tree trunk somewhere, feathers puffed up, trying to stay warm?

A break in the storms tomorrow will probably have birds out feeding again, but I worry about their small, feathered bodies in this cold storm today.

A fox visit to my deck

Before this series of storms hit, I had a special sighting. A healthy-looking gray fox tipped with orange fur walked along the railing above our deck, daintily balancing on the narrow ledge like an experienced tightrope walker. I was reminded that the California gray fox can even climb trees.

The fox walked to the corner, posed about a dozen feet from our window with its tail extended, and gracefully jumped down. I noticed it was a female. She then scampered up a steep hill and disappeared under some trees. We felt honored to have the visitation.

I’ve been thinking of how animals are adapting—or not—to the more extreme weather patterns created by climate change. January saw a large swathe of the U.S. under winter advisories, with temperatures dropping more than 25 degrees F below normal.

“Polar vortex” became a familiar term, and weather people tried to explain how the jet stream and the movement in the stratosphere affected temperatures on the ground. We’re still trying to figure this climate disruption thing out.

While temperatures on the Northern California coast rarely dropped lower than 40 F, a family member in Montana reported 40 degrees below zero— eighty degrees colder! Frostbite could affect the ears and feet of domestic dogs who went outside.

How do the local foxes and other animals survive? With some ingenuity. Shelter becomes more crucial than ever, along with food sources to keep body heat up.

What do we do in the name of Beauty?

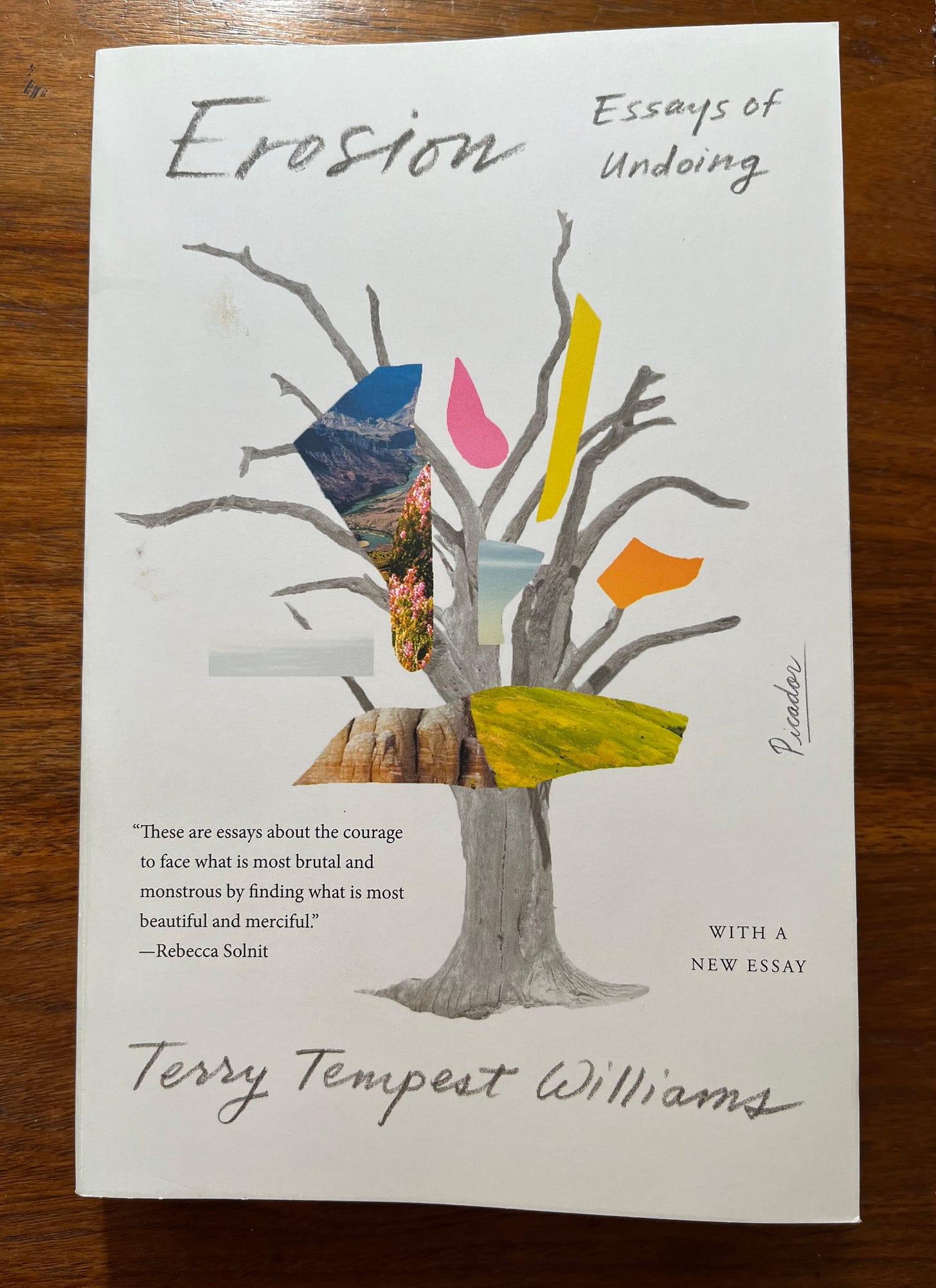

The wet winter weather and longer nights have me reading more. It’s a time to dip into the minds and words of people like Terry Tempest Williams. Her lyrical and eloquent non-fiction book, Erosions—Essays of Undoing, explores the various ways we face the often-numbing level of disruption happening on Earth.

Tempest Williams is a Writer-in-Residence at the Harvard Divinity School. She searches for the beauty yet to be found in the world, mourns the losses, and summons actions to protect places we love.

Her theme of erosion is encountered daily in the Red Rock country of Castle Valley, Utah, where she grew up and now lives half the year. Her writing is a reminder of the special connection between people and the places we love.

This [book] is a gathering of stories, poems, and pleas in the name of Beauty in an erosional landscape sculpted by wind, water, and time. It is also a book of questions. Whom do we serve?

Terry Tempest Williams

She tells a wide-ranging group of stories from Indian Country and beyond, “exploring the idea of erosion: the erosion of land; the erosion of home; the erosion of self; and the erosion of the body and body politic.” Her holistic approach to defining erosion resonates with our current times.

She tells compelling stories of courageous people defending their corner of the American West from the erosional pressures of oil and gas mining.

She befriends Native American tribal members and participates in a ceremonial Bluebird Dance against the erosion of culture and community.

She bravely recounts the erosion of mental health in her brother and his subsequent suicide.

She celebrates Sue Beatty, a biologist at Yosemite National Park who noticed the erosion around the Giant Sequoias of Mariposa Grove affecting the trees’ health. She then got the National Park Service to create a plan to save them from the damaging pressures of foot and vehicle traffic. The grove was declared off-limits for three years, pavement was removed, and paths were rerouted to help these iconic trees survive.

Tempest Williams muses about how our participation in defense of something can change us. “In the process of being broken open, worn-down, and reshaped, an uncommon tranquility can follow. Our undoing is also our becoming.”

She adds, “We are eroding and evolving, at once….I am trying to stay open to what is coming, understanding that uncertainty is the way of the world.”

How can we handle uncertainty?

Wild animals instinctually understand about uncertainty. They never know where or when the next food source will come, yet they trust that it will be out there somewhere.

Their attention is focused on the moment happening. For the most part, their trust is well-placed because Earth has been in a long, stable period, only recently veering into patterns of unpredictability.

We humans are less comfortable or tolerant of uncertainty. That will need to change as we learn to live with the cascading effects of climate. How do we adapt to more uncertainty?

Becoming better observers is a start. The scholar David Strayer says, “Attention is the holy grail.”

Only you will know where to direct that attention, but fellow Substack writer (An Irritable Métis), author, and poet Chris LaTray believes getting outside to experience nature is vital. Chris is a member of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana. He’s also the new poet laureate of that state.

He set himself a goal of being outside 1000 hours in 2023– in Montana, no less! This goal had him following tracks in snowy weather, drinking coffee on his sub-freezing porch, and exploring shaded forests or bodies of water when the sun scorched the land. He achieved his goal and says he will continue doing that practice in all weather since it feeds his soul.

The intelligences of the wild— what would the fox do?

Uncertainty will be a theme in the months and years to come, but as Terry Tempest Williams reminds us, we can reach out to others—both human and non-human— for support.

We need human endeavor and intelligence, but we also need the intelligences of the wild— the millennial authority of redwood trees, the forbearance of bison, and the lyrical sermon of a wood thrush at dawn.

Terry Tempest Williams

The multitude of species around us can instruct and inspire. The bold fox who jumped on my deck railing demonstrated resourcefulness and some bravery, entering the territory of humans as she searched for the peanuts we sometimes throw out for the birds.

In mythology, foxes represent cleverness and resilience, looking for opportunities and openings to thrive. They have to be able to “read” cues in the environment and assess risk. In folk tales and in life, foxes often outwit people and domestic animals in their pursuit of food, play, or other goals.

The video below shows a red fox playing with a domestic dog and another fox of a different breed. The red fox appears to be the one inviting and controlling the play.

Could our human race benefit from the fox’s light-footed curiosity and boldness as we enter the uncharted territory ahead? What might learning from a fox look like?

It may look like venturing to cross more boundaries, whether physical, cultural, or between various species.

It could also mean we need more acts of boldness to multi-solve the problems facing us. Instead of “Think outside the box,” another phrase for problem-solving could be “Think more like a fox.”

It may look like paying more attention to our natural surroundings. Wild animals, like foxes, all pay close attention to what’s happening since their lives depend upon noticing. If the human world had been doing that, we might be in a different place today.

And lastly, thinking like a fox means incorporating play time into every day. 🦊

As we face erosional pressures in our lives, perhaps we need to use more of these fox attributes: boundary-crossing, venturing boldly, paying close attention, and taking time to play. After all, the human race shares these characteristics too. 🧡

Robin Applegarth

Terry Tempest-Williams’ book Erosion, which is really a writer’s love song to the West, ends with these lines:

“Are we listening?

This is the Liturgy of Home.

There is only one moment in time

When it is essential to awaken

That moment is now.

Buddha

This does not require belief, it requires engagement.

How serious are we?”

I like to hear from readers

Is there a wild animal (or even a domesticated one) you like to observe? How do they live differently from us, and is there something to learn from that difference?

I like to watch whatever I can see, mostly that means birds and deer. Our local raven family is very tolerant and loyal to each other. Those are character traits I admire.

You can make a public comment at the button above, or respond to your subscriber email to reach me privately. You can follow me on Mastodon social media: @RobinApple@mastodon.social

If you liked this article, please hit the heart ❤️ button at the bottom or top as it helps more people find it on Substack. Thank you to readers who have referred the Mother E newsletter to friends and shared on social media!

Not subscribed yet? Mother E is a free newsletter about our connections to other species in a climate-changing world. Sign up below to have it delivered to your email box on the first Sunday of each month.

🦊🦊🦊

My cat came home covered with mud and hurting all over. Abscess costing $770 in vet bills. Could he have tangled with your fox? The injuries seemed to be more than from a cat fight.