Sheltering through a bomb-cyclone with a book on time

A coastal storm precipitates thoughts about climate adaptation and long-term planning

You’re at Mother E, a free newsletter exploring our kinship with nature in a climate-changing world. If you missed the last edition, it’s viewable here: Winter Awareness, Solstice, and Soulful Books

If this newsletter gets shortened by an email program or the images don’t show, you can read it on the website here. To get Mother E coming to your email box every other Sunday, sign up below.

I’ve taken a few weeks of break from publishing so I could visit family and recharge over the holidays. Returning home, my town was bombarded with a series of storms and long power blackouts.

You can read about my coastal town of Gualala, CA. having week-plus power outages in the NY Times, where a couple of us were quoted (bottom of page).

Fierce winter storms raise thoughts about future preparedness

I WAS BROWSING though the aisles of a big bookstore a couple of weeks ago while on a trip to see family. Among the many juicy-looking titles, this one jumped out at me: The Good Ancestor—a Radical Prescription for Long-term Thinking, by Roman Krznaric.

Since the first of a new year often prompts thoughts about the passage of time, I bought it and reviewed it in part two of this essay.

Our ideas about time are crucial to examine, since they have led us to the decisions (often short-term) that have precipitated the climate crisis. As a society we’ve chosen near-term benefits over longer-term vision and a way of life that’s sustainable.

Our culture is full of short-term actions: buy-now buttons, instant messages, fast food, single-use packaging. While these can be convenient, when short-term or short-sided thinking dominates government policies, health-care, education or community design, the results can be problematic or even dangerous.

For example, my coastal community has many trees, with mostly above-ground power lines installed decades ago weaving through those trees. When the region was hit by a lashing rain “bomb-cyclone” storm in the last couple of weeks, tens of thousands of trees were blown over, their roots unable to hold on to the water-drenched soil in high winds. The trees took down many power lines with them, leading to a wide-spread electrical outage. Our local power was down almost NINE days on my street.

This is not just an inconvenience. Millions of dollars of food has spoiled in the wider region this week, and medical emergencies increased as people struggled with cold, darkened homes, non-working appliances, closed roads, and storm damage. Some people died.

What if long-term thinking had been used when those power lines were installed? They might have considered that fierce storms coming from the ocean would disrupt services often in the winter, and then spent the extra time and money to install those lines underground. Even installing 50% of the power lines underground would have helped. I expect an underground electric install might have been both cheaper and safer in the long run than the system we have now.

This storm was a destabilizing hardship for thousands of people. Fortunately, neighbors helped neighbors, first responders eventually arrived from afar and worked through the rain, and our medical clinic strategically positioned ambulances on both sides of a river that later flooded.

We could do more to prepare for the next one, though. My community has many older residents, yet lacks a basic warming center or place to gather in emergencies. Our house got down into the low-fifties (OK, snow-country people, chuckle at a Californian’s cold-intolerance), and I was struggling to stay warm inside without any positive heat source. Knit scarves and cap, a big coat, and hot tea helped, but I wondered, how did young children, the sick, and elderly people fare? This storm demonstrated the wisdom of having redundancy for crucial things like heating and cooking. My house needs a wood stove which can warm and double as a cooking surface.

I called our electric provider, PG&E, after the power had been out for two days to ask when it might be restored, and where we could go to warm up. They told me the county had no public emergency center open.

What if rural communities like mine used medium-term thinking and designated a local building to be a resource center for emergencies? It could provide a warming center when power is out, a communications hub, a place to charge cell phones, and maybe serve hot soup. First responders would have a central place to refer motorists stranded by blocked roads or damaged homes. At other times, it could function as an earthquake center, fire evacuation site, or hot-day cooling site. Maybe it could even help the homeless. When times are tough, it’s a comfort to know one’s community has a place to connect and be supported.

Officials tell us these wet storms will increase in the future, since climate-warmed air holds more moisture than cooler air, and the jet stream has altered. Think of the storms/ heat we are having now and imagine them doubled or tripled in duration or intensity in the next ten years. Climate experts say fractional degrees of climate warming are logarithmic in their impact.

This raises questions—how can all our communities use longer-term thinking and planning to be better prepared? And specifically, what do your household and neighborhood need to adapt to this challenging future? When we join forces, we hold together, much as redwood roots intertwine to keep each other from falling.

What does it mean to be a good ancestor?

Roman Krznaric, a British philosopher and author of The Good Ancestor, makes a strong case for practicing “long termism” as a way to heal many of our current problems and leave a better world for those coming after us. His book is thought-provoking and full of revelations.

He cites some of the problems we’re facing now that could be improved by thinking across decades and centuries rather than just days, months, or several years.

Ecological breakdown (caused by an exploitative mindset that takes more from the planet than is replaceable/sustainable)

Intergenerational injustice (not thinking of the needs of future generations, as highlighted by Greta Thunberg and the youth movement)

Political short-sightedness (acting only within the next election cycle and allowing undemocratic processes such as lobbying and $$ to dominate.)

Speculative capitalism (short-term trading and views, not factoring in the external costs of making products with Earth’s resources)

Outdated education systems (modeled on the past rather than anticipating future needs)

Marshmallow brains vs. acorn brains

The author of this book cites the constant tug of war between our “marshmallow brain” that wants a pleasure or benefit now vs. our “acorn brain” that can plan and wait for larger future benefits that might even reach more people. Both types of thinking are needed to function, but the percentage of time we spend using our “acorn brain” needs to expand, he says, if our human species is to survive very long.

How do we cultivate this practice of being more aware of our own and humankind’s future needs and act from that perspective? Here are a few of his suggestions:

Deep-Time humility is the art of zooming out to get the big picture that humanity is but a small blink in cosmic history. When we visit a two-thousand-year-old redwood or the pyramids, many people sense this reverence for an expanded sense of time covering millennia.

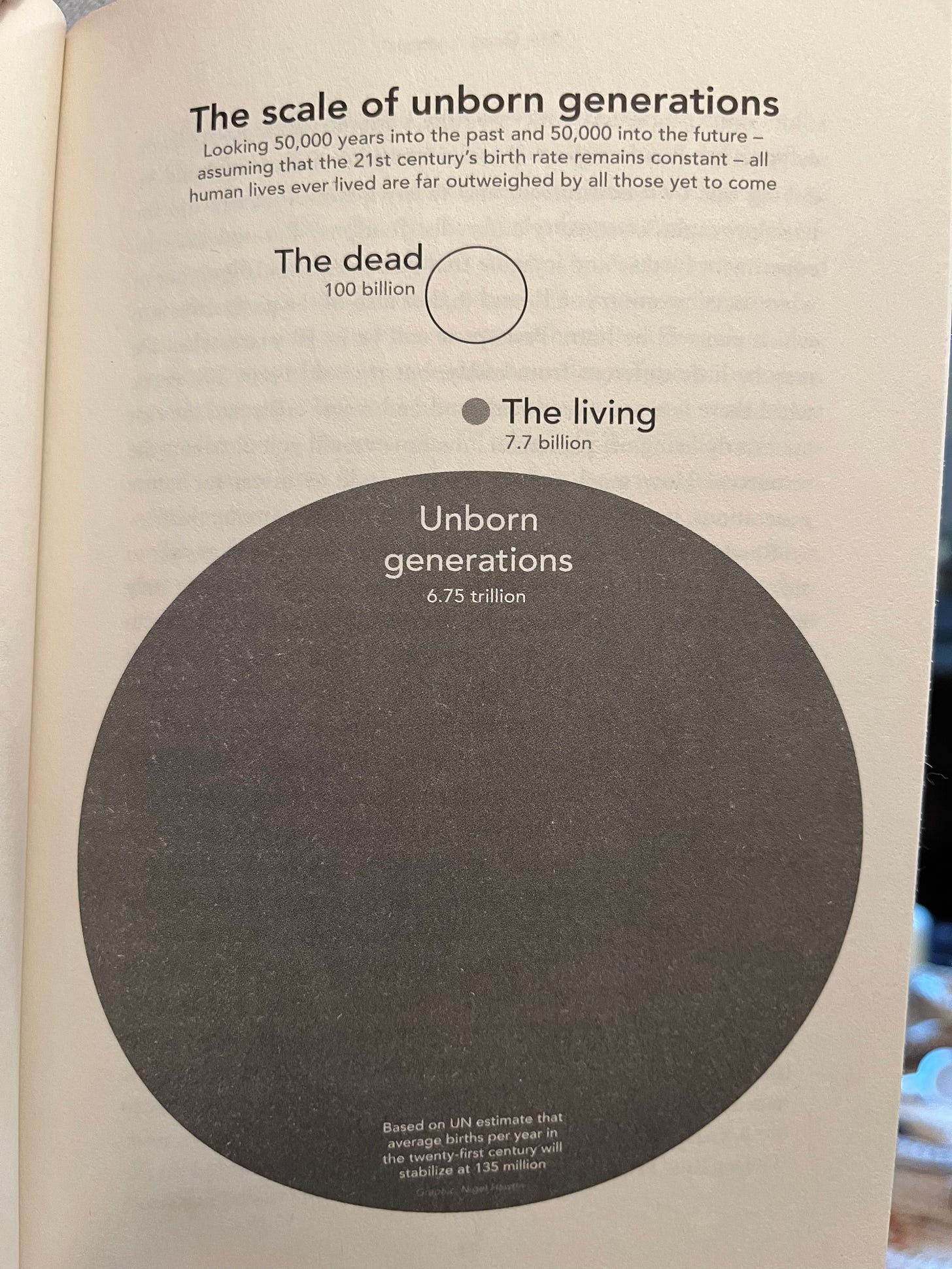

I took one look at the picture below in his book and felt an “Aha” moment. This graphic spans 100,000 years—50,000 years back and 50,000 years ahead. All the humans who have lived before us in the last 50,000 years are represented by the the small white circle at the top— the dead. The tiny dark circle in the middle is all the people alive today—the living (which is now 8 billion). The massive dark circle that takes up most of the page is the projected population of humans who will be born in the next 50,000 years—unborn generations. We owe them a livable world, as has been passed on to us.

Graphic by Nigel Hawtin, from the book The Good Ancestor, by Roman Krznaric.

Intergenerational justice is our ability to think about our descendants and future humanity as real people and to act with the “seventh generation” consciousness often practiced by indigenous cultures. What kind of a world do we want to leave for this seventh generation?

Cathedral thinking can help us act on projects with longer time frames that may even surpass our lifetimes. This is when generations of people hold onto the same vision to bring it to completion.

The Cologne Cathedral in Germany took 632 years to complete (1248-1880), or about 25 generations of people. The Great Wall of China began in about 400 B.C. and was constructed until about 1600 A.D., about 2000 years or 80 generations. The pyramids, aqueducts, city layouts, the Panama canal, and intercontinental railways are examples of projects where humankind used long-term thinking.

Those of us living today are the beneficiaries of long-term “acorn” thinking and efforts by previous generations. This includes the U.S. Constitution, the United Nations, the European Union, the public library system, national and state parks, museums, health research/advances, and much more.

All the human systems existing at our birth—both good and bad—were created by those who came before us. What will we leave for the ones who come next?

We can only plan for the future after making some educated guesses about the conditions we will face.

Holistic forecasting goes much longer and wider than normal. Instead of just thinking about the human species, it also takes into consideration all other species living with us on Earth over centuries.

It [Holistic forecasting] offers a much longer time frame than traditional forecasting, stretching into decades and centuries…and is also wider in scope, focusing on the big-picture prospects for people and planet on a global scale, rather than the narrow institutional and corporate interests that prevail in mainstream forecasting.

Roman Krznaric

Transcendent Goals inspire us. Humans thrive when we have long-term goals and a higher purpose. Ancient Greeks called this a telos. If the telos is not inspiring, it’s not big enough.

It functions as a compass for our thoughts and actions, helping us make choices among the sea of possibilities.

Roman Krznaric

Jonas Salk had a telos of finding a cure for polio, and the world benefitted from his work. Individuals may have a purpose or long-term goal of raising a loving child, advancing knowledge in a scientific field, advocating for climate action, improving a piece of land, following a religious practice, or helping a disadvantaged group.

There are as many higher purposes as there are people, but also whole societies can adopt a common goal.

Krznaric examines some of the transcendent goals human societies have followed, such as perpetual progress (“pursue material improvement and economic growth”) and “techno-liberation” and concludes that the only one that makes sense for our time now is the one that includes long-term survival, below.

“One-Planet Thriving—Meet the needs of all current and future people within the means of a flourishing planet.”

Success is keeping your offspring alive for ten thousand generations and more. That presents a conundrum because you’re not going to be there to take care of your offspring ten thousand generations from now. So what organisms have learned to do is to take care of the place that’s going to take care of their offspring. Life has learned to create conditions conducive to life. That’s really the magic heart of it. And that’s also the design brief for us right now.

Janine Benyus, biologist and biomimicry designer

What will our cathedral-thinking legacy be?

A gothic stone cathedral often took hundreds of years to build. Repairing our planet’s climate for human longevity may take even longer. While climate scientists are not sounding optimistic, neither do all of them believe the future is an inevitable climate collapse with human extinction.

If we can quickly pivot to longer-term thinking—planting the “acorns” now for the future we want in fifty or 200 years—the future can be altered for the better. We’ve adopted new ideas and mobilized impressively before, so it is possible.

We can’t simply wait and hope for new technology to solve this multi-faceted climate crisis. Technology and high energy demands brought on some of the very problems that created global warming and there’s no evidence it will pull us out.

Time is our medium

Ideas are the energy and action is the coin we spend to leave a lasting legacy of a livable world. Time is the medium we use, as we stretch to include the eons to come.

What if we succeed? Our timely intervention will have given many future generations a reason to think of us as good ancestors.

Robin Applegarth

To stretch your brain into deep time, think of what life might be like 10,000 years ahead, in 12023 A.D. Then, add a zero in front of this year to show the connection.

This was written in the year 02023 A.D.

I like to hear from readers. What causes you to think longer-term?

And if you live where winter storms are battering, what insights have you had about preparedness?

If you’re not subscribed yet to Mother E, you can sign up below to get insights every other Sunday on our relationships to other species in a climate-changing world. It’s free. Robin

Loved this article. My thoughts have always been so much more about the future than the past. It’s human nature that creates much cynicism as much of that nature is based on short term survival and immediate gratification.

Thank you Robin. I have to say though that I cannot fathom the potential for 6.75 trillion humans in this planet's future. Mankind is working way to hard to kill the planet - I think earth is going to have the last bittersweet laugh.