Sea Forests- Kelp's Peril and Promise

Bull kelp off the California coast--efforts to save it increase

You’re at the free, Mother E Newsletter— telling the stories about our connections to other species— and what that means in a changing world.

Last time, I featured redwood forests— Defending the Trees They Love. This time, we’re looking at under-the-sea forests. Get Mother E coming to your inbox every 2 weeks at the button below.

EVERY OTHER BREATH YOU TAKE is courtesy of the oceans.

Think about that. The seaweed and phytoplankton in the oceans make about 50% of the world's oxygen through photosynthesis, similar to how trees create oxygen on land.

Take a breath—thank the trees. Take another breath—thank the oceans.

But the oceans' kelp, the largest of its seaweeds, is in trouble. The oceans are growing warmer and more acidic as they absorb the excess greenhouse gasses we produce. Warmer oceans hold fewer nutrients for the kelp forests, leading to their losses. An added threat has been the sharp increase in purple urchins, which have been quickly chewing through the kelp.

Kelp— live fast and die back yearly

Bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) has a life cycle encompassing one year, growing from a tiny spore to as high as 130 feet tall-- the height of an eleven-story building. It's a macroalgal seaweed and one of the few ocean species we can regularly see and touch. It's slippery, substantial, strong, and can grow up to a foot per day.

It attaches to the rocky seafloor with strong holdfast anchors. Kelp stays afloat with gas-filled bladders, which keep the fronds near the surface to gather sunlight.

Its brown-green ribbons sway in the currents in a graceful dance, shifted by tons of cold ocean water. Fish slide into its shadows to hide, using it for both habitat and food sources. If you watch curling waves, loose kelp may show up backlit as a dark sea-serpent shape.

Like forests on land, kelp forests nurture many hundreds of species, from invertebrates to fish to marine mammals. They are one of the ocean's most life-filled ecosystems and provide a place for young fish to thrive. Healthy kelp forests also help protect the coasts from tidal surges and erosion by slowing down the water and acting as a protective barrier.

I first learned about the troubles of offshore kelp forests at a live lecture a couple of years ago by Dr. Cynthia Catton, a marine biologist working at the University of California, Davis's Bodega Marine Laboratory. She presented a PowerPoint of the changes. Where there had been lush underwater forests of bull kelp before 2014, there were now emptier waters with millions of purple urchins carpeting the seafloor—an "urchin barrens."

Zombie urchins cover the coastal seafloor

In this out-of-sight problem, a formerly rich coastal ecosystem had collapsed with little public notice. The purple urchins had exploded to sixty times their average population, leaving hundreds of millions of empty, hungry urchins that could go into a dormant "zombie" state and survive for many years.

The bull kelp’s reproductive cycle is part of the reason it’s having trouble coming back. Spores need to grow fast in cold nutrient-rich waters, followed by normal annual dieback. This makes it challenging to regain a footing now on the urchin-infested seafloor.

Other factors in the kelp's die-off included a wasting disease in sea stars, especially the sunflower sea star, which ate the purple urchins that were now chewing up the kelp. These sunflower sea stars used to be abundant but are now critically endangered on California’s coast.

Kelp losses have caused die-offs in shorebirds and marine mammals too. These species depend upon fish whose populations have dropped due to sea forest disappearance.

Interconnected ocean species means a change in only one or two species can affect the whole ecosystem.

Slightly cooler waters in 2020-21 brought an improvement in kelp growth, but over 90% of the original coastal bull kelp forests are still missing from the northern California coast. Hundreds of species who lived in them were affected. One of those species was abalone, a large edible sea snail (and prized seafood delicacy) that depends on kelp for food and habitat. It found itself stranded and foodless.

"We started seeing a lot of abalone, which normally would have been hidden, boogying across the rocks, looking for food. And purple urchins came out of their crevices...and became a lot more aggressive." Dr. Cynthia Catton, marine biologist

The impacts of kelp loss and abalone populations collapsing were felt by people regionally. California Department of Fish and Wildlife has had to close the abalone recreational fishery until 2026 or later to give abalone a chance to recover. This has had a ripple effect in the coastal economy, with estimated tourism losses from $24 million to $40 million per year in Northern California.

Following strands of the kelp story

My son and I took a trip north to coastal Fort Bragg in 2019 to see some of that impact. We wondered what actions people could take to help. The town was a primary gathering spot for thousands of recreational divers in the past. We stopped by the local dive shop where the owner told us his quiet store used to be bustling with activity.

During the 25 minutes we were there in July, only one person came in, and the row of wet suit changing rooms was empty. "Ab diving" had been a way of life for multiple generations of the owner's family. Faded photos of smiling divers holding trophy-sized abalone lined the walls. It was a sad reminder of how climate change can alter human and sea creatures' lives in a few short years. The only dive shop in town (and the region) is now out of business.

My son, Ethan Applegarth, created the photo video below from our trips to follow the kelp/urchin story. You'll see volunteer wet-suited divers removing purple urchins, as that’s one action we can take to help kelp. There's a visit to Fort Bragg's Noyo Center, where the director gave us a tour of the new dome ocean theatre and discussed their “Help the Kelp” program. We watched an urchin collection boat chug in to dock and offload crates of the spiny urchins, glistening in the sunlight.

The kelp story is ongoing, but the current losses are sobering. Human actions are like ripples in the water. When we're unconscious of the effects we make, or uncaring about the welfare of non-human species, those ripples can turn into a tsunami wave.

Resolve, restoration, and urchin farming

What is being done now to restore the kelp that should be living off western coastlines? Dozens of organizations with diverse missions have now formed alliances. The Greater Farralones Kelp Recovery Program and the KELPPER consortium group are key players. Anyone can listen in to their monthly calls and get involved.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is working with scientists to collect a spore bank of coastal kelp, hoping to identify some that are more resilient in warmer waters. Experts estimate that ocean warming is here to stay, likely for decades or until our efforts to reduce greenhouse gasses make a difference.

Recreational and commercial diver groups have made diving forays into kelp “oasis coves” to remove thousands of purple urchins at a time. Commercial uses for these spiny purple invertebrates are still being discovered. Some get combined with compost or used for calcium in fertilizer.

Efforts to bring back the sunflower sea star (which eats purple urchins) center around captive breeding programs to find more resilient varieties of sea stars.

Finally, one of the solutions might be for humans to take a bite out of the urchin population. The urchins now living in the urchin barrens are hungry. The edible part of them, the uni, is tiny. But when they are collected and fed up for about eight weeks— through aquaculture "urchin ranching"—they become commercially viable as a specialty food.

Uni is a delicacy in sushi restaurants, and I have eaten uni sauce over fish— delicious. Urchinomics is a global commercial business collecting and growing urchins for food. (Their website has some interesting underwater videos of kelp.)

New Kelp Act bill — See good news update below this article!

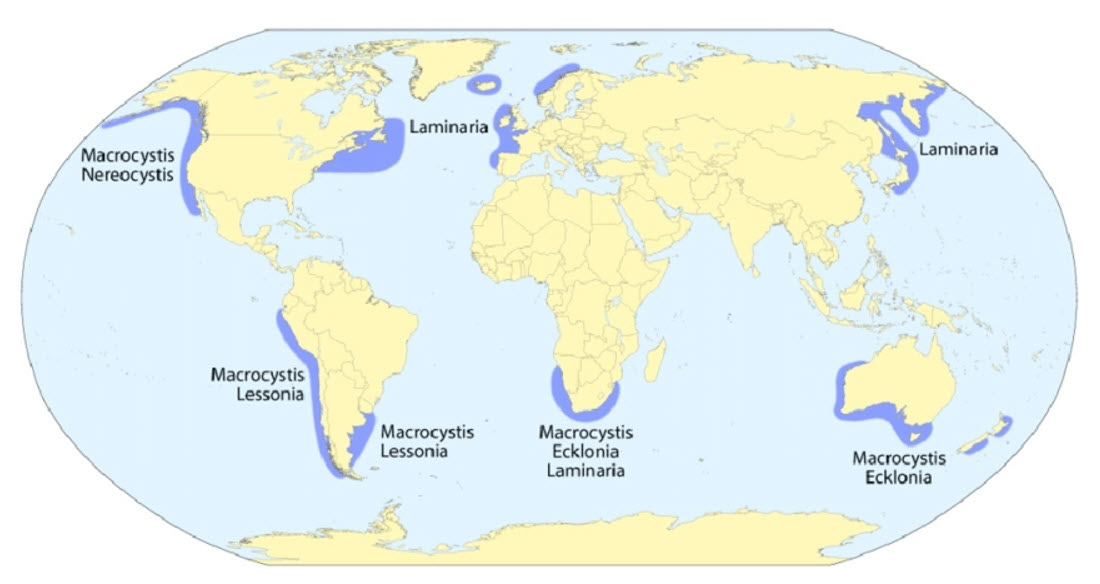

Kelp forest loss is not limited to California. Kelp die-offs have happened in Alaska, Australia, Tasmania, UK — some of the places where cold water kelp live. The map here shows the kelp distribution across the planet. Healthy kelp forests still remain in some of these regions.

Creative solutions are underway worldwide to help the kelp with involvement from scientists, entrepreneurs, students, and resourceful citizens. Human ingenuity and partnerships are needed more than ever before in these changing times.

What we've learned, though, is that it's far better not to stress nature's interconnected systems in the first place— than to try to restore damaged, complex ecosystems we don't fully understand.

The oceans of our planet create half the oxygen we all breathe. They are the blue-water birthplace of life and deserving of our attention.

If we have room for one more acronym perhaps it's this— KELP reminds us to Keep Earth's Lifeforms Protected. That nurturing of other life is what kelp forests have been doing in their part of the ocean for the last twenty million years. Now, they need some nurturing back.

Update!

As this article goes to press, U.S. Congressman Jared Huffman has just sponsored a Kelp Act bill to provide federal funding of $50 million per year through NOAA grants. The bill will promote kelp restoration in northern California. The bill is so new, it has no number yet.

Not subscribed yet? Use the Subscribe button below to get Mother E coming to your inbox every two weeks with stories of our connections to other species in these changing times. It’s free!

Thanks for reading! As always, I appreciate your comments. You can reach me by responding to the email you got as a subscriber, commenting on the website at the button above, or on Twitter @RobinApplegarth

Robin A.