Letting Life Move Freely

A dive into migrations and their importance for Earth's species | What happens with curtailment of movement?

Welcome! You’re at Mother E, a monthly newsletter devoted to exploring our kinship with other species in a climate-changing world.

You can also view this post on the website if the photos don’t show. And if you missed last month’s post, it’s here: The Summer that Challenged People and Wildlife

Mother E readers:

The post that follows was inspired by a seemingly unrelated group of articles and essays I had been reading, when it hit me that they all related to movement. While we can travel halfway across the world in a matter of hours by plane, land-based life seems to have more barriers to movement now than it had 50 or 500 years ago, unless it’s hitching a ride on cars and boats. 😏 Here’s my not-fully-explored yet thoughts on migration and how it connects humans and animals.

Robin A.

IT CAN BE HARD TO SEE OUR CONNECTIONS and common needs with other species sometimes. For example, what do whales, birds, wolves, and humans have in common?

The articles I was reading about them all pointed to the need to move freely across the landscape (or seascape) for survival.

Here’s a dive into the topic of migration and movement—or limits to that freedom of movement. This subject is a crucial one for the next decade as we grapple with how to save as many of Earth’s species as possible.

What happens when migration encounters barriers: physical, environmental, political, or cultural? The free flow of animals, and even people, can be interrupted these days in so many ways.

Where are those millions of birds going?

High over our heads, migrating birds are on the wing this fall. For some of these birds, weather-related events such as hurricanes can blow them off course. Flamingos showed up on chilly Lake Michigan in Wisconsin in September 2023. Audubon experts suggested Hurricane Idalia blew them off course. Less fortunate or smaller birds can get pulled into the storm and perish.

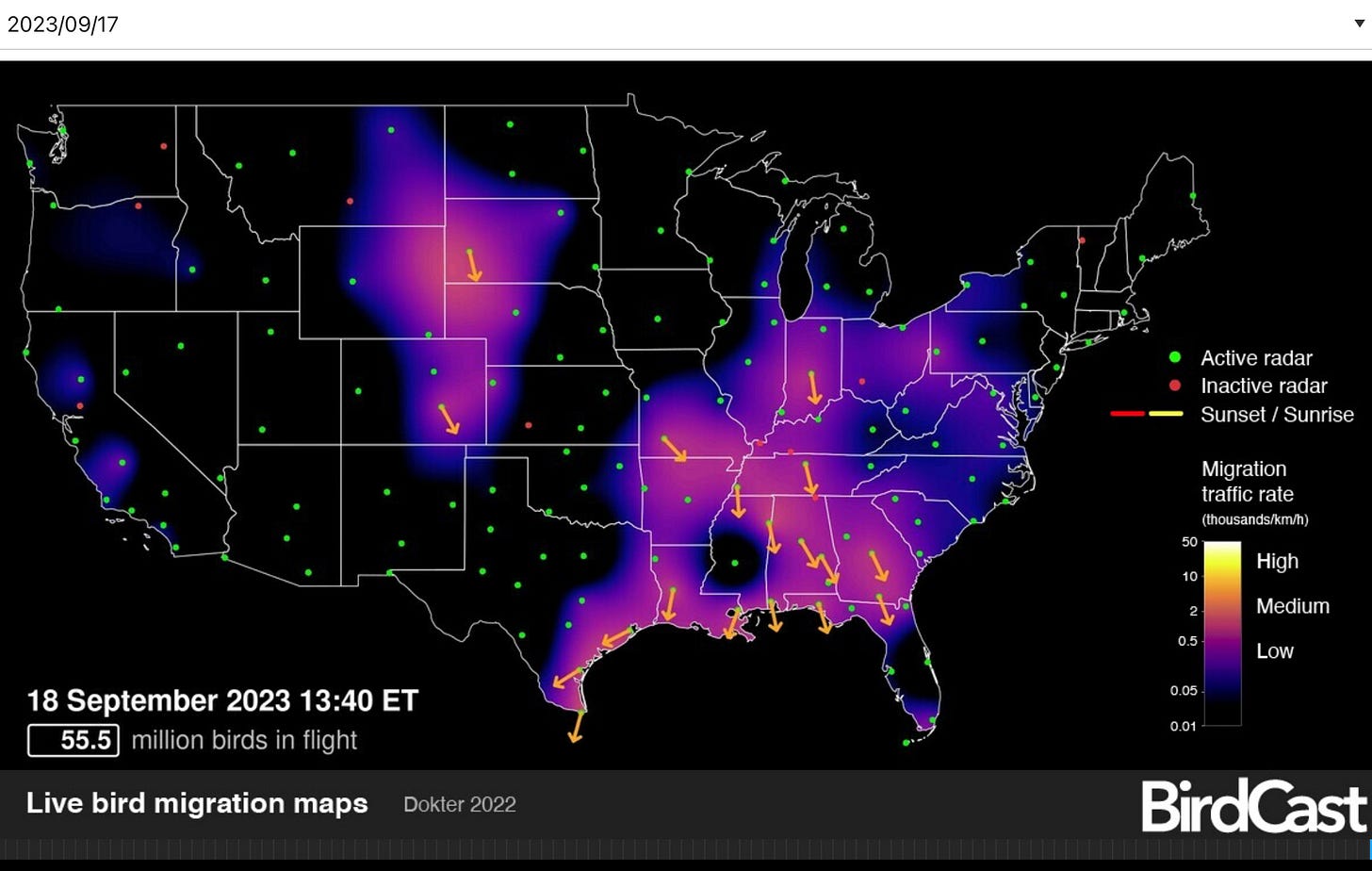

You can check out where these millions of migrating birds are traveling by looking at the BirdCast map, an app that uses U.S. weather surveillance radar to detect the quantities of birds overhead from sunset to sunrise.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which helped develop this tool along with Colorado State University, says that three hundred million birds will be in flight across the U.S. on their journeys to warmer winter climates each night!

Below is a screenshot of bird movement on one night in September. This BirdCast tool makes visible the invisible nighttime bird migrations that are so much a part of our living planet.

The humans who rely on migration for existence

Why is movement across the Earth's surface so crucial to living species?

Life moves to find food, more habitable territory, mates, or even new adventures. You might relate to that wandering quest if you've lived in more than one place. Differing needs may have caused you to move, just as animal species do.

Our human ancestors roamed freely, starting with early hominids on the African continent and flowing into other world regions. Without migration, there would be no human population on different continents.

Here's a richly-told story from Emergence Magazine: A Whale in the Desert, Tracing Paths of Migration in Turkana. It connects early hominids, the fossil history of Northern Kenya, and a present-day Turkana herder. This nomad talks about the importance of free movement and migration for his family's survival in that challenging desert region.

It caught my attention because I've traveled through that starkly beautiful volcanic land and seen herders moving their small groups of goats or bony cattle across the landscape. Their lives depend upon the animals and their combined skill in finding food and water sources. Migration is vital to their existence.

The African Union reckoned a decade ago that one in four Africans were pastoralists. This is no arcane livelihood, but one that uses mobility to survive in environments characterized by erratic rainfall and frequent scarcity, where more settled lives are impossible.

Tristan McConnell, A Whale in the Desert

Whale migrations through ship-studded waters

Whale movement and lives have been affected by the fleets of ships that roam the ocean. A fourfold increase in ship travel, mainly large container ships delivering goods to the West, has caused an increase in whale deaths.

An estimated 20,000 whales are killed every year, and many more injured, after being struck by ships—and few people even realize that it's happening.

Brandon Kim, Why Ships Kill Thousands of Whales Every Year, Nautilus Magazine

Why is it more of a problem now? Ships are being built larger and are traveling at a higher speed. When whales encounter these fast-paced mega-ships, it's like being hit by a steel wall in the water. The whale usually loses, and ships are so big they often don't even know they've run over a whale.

The 53,000 global ships navigating the world's oceans transport the things we buy from China or overseas countries. Unfortunately, there is a cost to whales and nature for our consumption.

There are solutions, though, such as routing ships away from frequent whale travel corridors and slowing down their speed so the whales have a chance to get out of the way. Slowing down our consumption habits would help save lives, too, as it would mean fewer ships colliding with whales.

Here’s a new documentary movie, Collision, from Ocean Souls Films, which tells the dramatic story of whale strikes and the solutions. The movie trailer, with stunning photography and interviews, can be viewed on Amazon Prime and Vimeo: https://www.oceansoulsfilms.com/collision

Gray wolves and human refugees—fighting for ways to survive

We can no longer take free movement for granted in our more crowded and politically charged world.

All species seek to flow naturally from areas of less food/opportunity to areas of more food and advantages. Yet, physical, political, environmental, and even cultural boundaries often hinder movement in modern times.

The gray wolf is one example of a threatened animal that used to roam over hundreds—even a thousand plus miles. Wolves’ population has been curtailed by some state laws that encourage hunting, and the narrowing down of safe and protected habitat to places like Yellowstone National Park.

Migration in the human world is also complicated. You've probably seen photos of refugees who risk their lives to move. Climate changes and political instability have caused a global refugee crisis. The U.N. lists over 110,000,000 (that’s 110+ million) refugees in 2023. Those that survive may end up in refugee camps, imprisoned as illegal migrants, or bunched up outside the borders of a country.

On the southern border of the U.S., Mexican and Central American families have huddled recently hoping to cross into the U.S. Here is a photo essay of what it's like when migrating families with children encounter borders. The search for a livable home can be a fraught and emotional journey.

Whatever your thoughts are on the topic of immigration (a word which derived from migration) we need to recognize that there are compelling reasons that drive humans to leave their homes. It’s often hunger, danger, or lack of opportunity to thrive. Anyone on our planet could be in that situation someday.

The orca that almost swam free

If you've followed the story of the orca named Tokitae (formerly called Lolita), you would be saddened to hear of her death on August 18, 2023, so close to plans to release her back into the waters of her birthplace, the Salish Sea of Washington state.

Tokitae was a southern resident orca (Orcinus orca) who spent 53 years in captivity, performing a killer whale show every day in the Miami, Florida, Sequarium park. She inspired an end to the capturing of orcas from the Pacific Northwest and was the last southern resident orca held in captivity.

Her story is also one of movement, in this case, the curtailment of movement— the forced incarceration in a small tank only as deep as her length. If her life teaches us anything, it must include an awareness that other creatures deserve the freedom to live out their lives within their natural environment, with freedom of movement amongst their own kin.

Orcas have a tight-knit family unit that swims together, hunts cooperatively, and often keeps a lifelong close bond. The population of southern resident orcas has dropped to only about 73 left due to factors like the lack of Chinook salmon, polluted waters, and underwater ship noise, which hampers their ability to hunt.

The orca Tokitae had many allies and friends, though. The Lummi Nation of indigenous people in northern coastal Washington state advocated for her release, performed ceremonies for her animal spirit, and, after her death, brought her cremated remains back to San Juan Island for an emotional farewell gathering.

In a haunting moment, a recording of what was said to be some of Tokitae's last calls, recently made in her tank at the Seaquarium, was played over a loudspeaker. Also played were the wild sounds of her family members, recorded as they swam the waters of the San Juan Islands, where they gathered the day she died.

Lynda V. Mapes, Celebrating the life of Tokitae the orca on San Juan Islands, Seattle Times

Interestingly, the day of Tokitae's death in Florida, there was a rare super-pod of southern resident orcas which gathered at San Juan Island in Washington, where Tokitae used to live. Was this a coincidence—or a form of whale communication? There is so much we don't know about the inner world of whales and other creatures.

Honoring the ability of people and animals to move freely

Freedom of movement can equal life and more vitality, both for humans and for the animal kingdom. All species need more support in the challenging times we face, with more extreme weather events and parts of the planet becoming less habitable.

Biodiversity losses aren’t talked about widely as a human problem, but the World Economic Forum’s 2022 report says it’s “the third most severe threat humanity will face.” The loss of habitat and barriers to movement are part of this species-loss problem.

One solution may be to do more re-wilding, with the Half-Earth Project model proposed by the famous biologist E. O. Wilson. It seeks to curtail losses by proposing half of the planet's surface be set aside for wildlife habitat, with connecting corridors for freedom of movement.

Re-wilding would benefit people too, as the increase in plant mass would remove more CO2 greenhouse gas and provide enhanced recreational opportunities in addition to protecting the larger “web of life.”

Migration across landscapes has been a necessity for human, animal, and even plant life throughout Earth's long history.

Should we now consider more ways to open up artificial boundaries and reduce man-made barriers so people and animals can flow where they need to go for survival? In the end, our goal should be to do whatever we can to enhance life on Earth. 🌎 💚

Robin Applegarth

I like to hear from readers!

What’s on your mind related to movement, migration, or the plight of refugees?

You can make a public comment at the button above, or respond to your subscriber email to reach me privately. I’m no longer active on Twitter, but you can follow me on Mastodon social media: @RobinApple@mastodon.social

If you liked this article, hit the heart ❤️button at the bottom or top as it helps more people find it on Substack. Thank you to readers who have referred the Mother E newsletter to friends and shared on social media!

Not subscribed yet? Mother E is a free newsletter about our connections to other species in a climate-changing world. Sign up below to have it delivered to your email box on the first Sunday of each month.

Read more about the US Navy's sonar use which is dangerous effects on whales and dolphins in the book, "The War of the Whales," by Joshua Horwitz. Our finned friends need help.

Brilliant ❤️