This is the bi-monthly edition of Mother E, where I explore relationships between humans and the rest of nature. If you’re new here, welcome! Robin Applegarth

If you missed the last Mother E post, “Singing Across Oceans”, here it is. It’s FREE to subscribe. Join me in an adventure of discovery.

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better” Albert Einstein

THE SEARCH HAS INTENSIFIED. As we all tilt into the headwinds of the climate crisis, we’re also ramping up the search for solutions to protect ourselves and our earth-home.

One of those places to search is looking deep into the heart of nature.

Why look to nature for solutions? Life has existed on this planet for about 3.8 billion years longer than modern man. Janine Benyus, the woman who coined the word “biomimicry” wrote in her groundbreaking book, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature:

In that time [3.8 billion years], life has learned to fly, circumnavigate the globe, live in the depths of the ocean and atop the highest peaks, craft miracle materials, light up the night, lasso the sun’s energy, and build a self-reflective brain. In short, living things have done everything we want to do, without guzzling fossil fuels, polluting the planet, or mortgaging their future. What better models could there be?

Enter nature’s helping hand— biomimicry. What is it? It’s a process of asking, “What would nature do to solve this problem?”

Biomimicry is the practice of looking to nature for inspiration to solve design problems in a regenerative way. The Biomimicry Institute

Giles Hutchins, author of TheNatureofBusiness.org tells us, “A small leaf quivering in the breeze high up in the tree, has more sophisticated innovation packed into it than nano-computing or big data.”

Others agree. Janine Benyus adds, “We are surrounded by genius.” The video here is a two-minute explanation of biomimicry in her words.

Here are a few examples of products designed with biomimicry:

Wind turbines inspired by the aerodynamic fin of a humpback whale

Japanese “bullet” train with a sound-reducing nose design based on a Kingfisher’s beak

Adhesives strong enough for a human to stick to a window, inspired by gecko’s toes

Bird-safe glass with reflective strands based on spider webs, to avoid bird collisions

Light-weight building materials based on the strong, space-efficient hexagonal shape of the honeybee’s hive

Super-slippery coating for inside water pipes, copied from carnivorous plant leaves

Why is nature’s design crucial now?

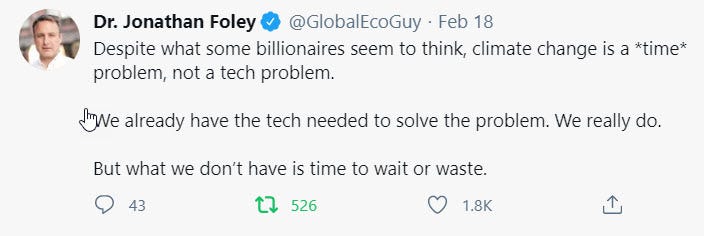

We are in a race against time to create a sustainable and regenerative world. Jonathan Foley is the Executive Director for Project Drawdown, listed as “The World’s Leading Resource for Climate Solutions.”

In February 2021, he tweeted this reminder about the urgency of time, saying we need to cut in half our CO2 emissions in the 2020s and pursue every avenue to do that.

To speed things up, we need to look to other species, our “biological elders” for advice, and think in whole-system ways. We need to redesign the way we farm, the way we transport ourselves, the way we interact with forests and other species on this planet. It will be a wholesale redesign of our world to meet the United Nation’s 17 goals for a better and more sustainable world.

It’s time to ask nature

The Biomimicry Institute offers this thought:

The human-constructed world is ripe for a deep redesign, and this time, it needs to be good for all life. Fortunately, we are surrounded by experts in life-enhancing design— the organisms and living systems that have been developing in an epic give and take for billions of years. What’s stopping us from learning from them is the lack of tools to transfer knowledge from nature to human design. We need a Rosetta Stone between “biological blueprints” and modern design of products, processes, and systems.

If you haven’t heard of the Rosetta Stone, it’s a famous archeological discovery from Egypt that provides a translation guide for Egyptian hieroglyphics, with ancient Greek and another language. If you know one of the languages, you can decipher the other two.

We now need another guide to help us figure out nature’s secrets. That code won’t come in the form of a written guide handed down from the past. It will be based on elevating the art of observation—becoming more aware and tuned into the many life forms around us, watching to see how they have lived their lives in sustainable ways for millions of years. It will also be based on sharing those observations and collaborating between ourselves and non-human species.

By combining human ingenuity with nature’s genius, the possibilities are infinite. The Biomimicry Institute

Copying nature--as old as time

When did the biomimicry design trend start? I’m guessing that humans have been observing nature and copying its designs and methods for thousands of years. Fishing nets might be based on observing spider webs. Early human mud-and-stick huts were likely based on observations of wasps and other creatures that used sticks or mud for shelters. Ancient Greek columns were modeled after sturdy tree trunks.

Next, let’s look at some fascinating buildings that have used biomimicry.

Buildings inspired by sea sponges and insects?

Biomimicry has been used in architectural design to make buildings more energy-efficient and strong.

Global warming will cause new challenges for us as the planet heats up. It will not be sustainable to just pump up the air conditioning around the world.

One creative architect addressed this cooling problem by designing an innovative shopping mall inspired by termites. Yes, you read that right—termites. The Eastgate Centre is located in Harare, Zimbabwe, in Southern Africa.

Architect Mick Pearce was intrigued by the termite’s ability to keep their tall, mud, mound homes at an even 31 degrees C, using a series of vents which the termites plugged or left open to draw a draft of air. See this three-minute National Geo video about using the same cooling method at the Eastgate Centre, with vents that open and close to regulate temperature. And since biomimicry design is sustainable, this shopping center operates at about a tenth of the cost, and with 35% less energy than similar buildings around it.

Another unusual building example sits in London, UK. The 590 ft. tall tower, dubbed “The Gherkin,” has an air ventilation system based on anemones and sea sponges.

The Gherkin mimics the shape and lattice structure of the sponge to do in air what the sponge does in water. The round shape of the building reduces wind deflections and creates the external pressure differentials that drive the natural ventilation system. Steemit.com, “Biomimetic Architecture: The Gherkin”

Biomimicry embraces life processes too

It’s not just products and buildings. Nature can also show us better ways to do things so we can withstand the inevitable shocks life throws our way. The 21st century is bringing a number of shocks and challenges, from weather crises to mass extinctions and disease pandemics.

By looking to how nature confers resilience on its systems, incorporating diversity and embodying resilience through variation, redundancy, and decentralization, we can create human-built systems that are inherently resilient to disturbances, even the unexpected. The Biomimicry Institute

We need all the help we can get. Why not use the oldest teachers on earth?

Nature decides what grows, using chaos

Down in Brazil, the people of the Xingu region have received help from NGO Conservation International to reforest degraded and burned land around the Amazon forest. But access to these remote areas and the distance from tree nurseries make tree-planting a difficult endeavor. Enter a new technique—muvuka. It’s a slang Brazilian word meaning something chaotic, crowded, or messy.

The process starts with locals collecting 100-200 kinds of native tree, shrub, and food seeds, and mixing them together. The seed blend is then added to some soil and mixed in a pile. After that, it’s tossed by hand over the degraded or burned fields.

In nature, many types of seeds fall on the ground. This muvuka video demonstrates that same technique, which contributes to more diversity and density than tree planting alone would do.

The seeds compete for space, and those that take root and thrive are the ones that will be adapted to that area. Nature decides what works there, and so far, over 1.8 million more trees have grown from the muvuca process in the last few years.

Apart from its positive impacts on biodiversity, muvuca addresses social and economic challenges such as food security and livelihoods. Mauricio Bianco, senior vice president of Conservation International

How can we apply biomimicry to our lives?

There are three essential elements for biomimicry, from the Biomimicry Institute:

Emulate—Copy a form or process found in nature

Ethos—Be sustainable, safe, and compatible with the rest of life

(Re)connect—Form deeper connections with other people and nature

Want to see how it all works in practice? Try out this free “30 Days of Reconnection.” The Biomimicry Institute is also hosting a design challenge contest open through April 2021 for people who want to try out new ideas and help meet the UN’s goals for sustainable development. It’s open to everyone, and challenges us to be part of the “1% solution.”

To become better observers, get outside the four walls of your home or office and spend regular time in a neighborhood, park, or the wild. Observe the plants and animals around you. How does nature communicate? What are the birds or squirrels eating? What relationships or interactions can you observe between species?

I noticed recently that the local raven family of 3 seem territorial and chase away other ravens, and that they are scavengers that drop somebody else’s spaghetti into my fountain. Their deep black feathers are shiny. I wonder, is this due to a water-repellent natural oil on the feathers? The raven family seems to have supportive relationships with each other, co-feeding their young and grooming each other companionably.

What do you notice? Biomimicry challenges us all to be better observers and live in more sustainable ways. Here are some of the questions we might ask:

How can we create less waste? Nature recycles everything.

How do we bring our food sources closer, more local, and expand them for resiliency?

How do we foster better relationships with people and non-human species that sustain and support us?

How do we live more lightly on the planet, leaving enough for other species as well as future human generations?

Maybe what we need today is a “muvuka of ideas” to redesign our society and replace the habits that have been harming nature with new habits that support life at all levels.

We need to collectively get together, throw in the ideas—the seeds—to a common pile, and see what takes root and thrives. It’s a messy process of cross-pollination, but the deeper connections and roots we form will be worth it.

Biomimicry promises to more quickly ramp up the needed solutions to help our suffering planet.

Megatrends author and futurist John Naisbitt predicts, “The greatest breakthroughs of the 21st century won’t occur because of technology; they will occur because of an expanding concept of what it means to be human.”

Perhaps, what it means to be human is to finally develop an awareness of where we sustainably fit into this complex, intelligent planet with millions of other species, and to work in tandem for a thriving future for all life.

Are you reading this but haven’t subscribed yet? I invite you to subscribe to the FREE Mother E newsletter. Twice a month it brings you thought-provoking ideas related to nature, climate-crisis and ecology. Feel free to share too! Thanks, Robin