An outer and inner tour of a forest

A walk through a redwood forest brings reflections on what forest-communities do for us.

Welcome Back! You’re at Mother E, a monthly newsletter devoted to exploring our kinship with other species in a climate-changing world.

You can also view this post on the website if you want to see the images better. And if you missed last month’s post, it’s here: The Making of a Feast in 19th Century Frontier America

This month, I’m taking you along on a visit to a coastal redwood forest property in the hills of southern Mendocino County, CA. With the help of a local land trust, we’ve applied for a grant to raise funds to protect it. These forests are not immune to the ax. Every time I visited recently, I passed a logging truck loaded with cut redwood trees taken from a nearby parcel. There is an ongoing push by corporate logging companies to extract as much timber as possible. Somewhere along the way, we forgot about forest preservation in the human quest for profits. These times call for a renewed effort to save the forests again.

Robin Applegarth

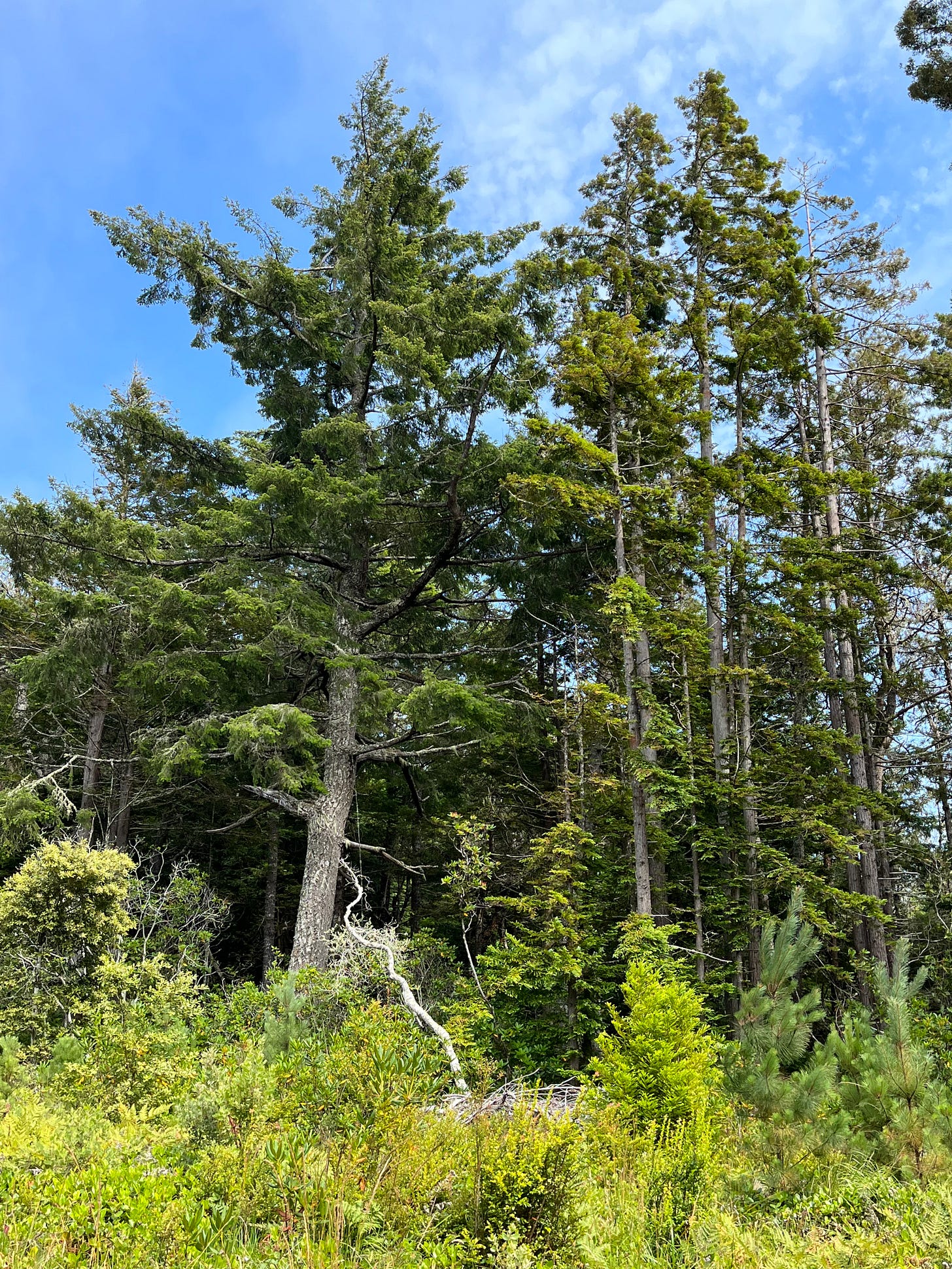

I RECENTLY TOOK A PARTY OF SIX PEOPLE on a multi-acre walk through a coastal redwood forest (Sequoia sempervirens) that I help monitor.

We were looking over the property to identify some plant species and forest conditions as one step in a grant application. The goal is to raise funds to put a conservation easement on the almost 40 acres and protect it from destructive commercial logging forever.

It was interesting to see what my visitors paid attention to. When in wild places, what jumps out are any anomalies, like something manmade— an old wooden sign, a weathered fence post, or a heap of boards peeking out of pine needles. We notice the things that indicate other humans were there before us.

Wild mushrooms also drew people’s attention. The rainy season is just starting here on the Mendocino coast, so we all stopped to look at a field of tiny gray parachute-shaped mushrooms, a tall, white shaggy-mane fungi, and a row of caramel-colored mushrooms. We even found a banana slug eating some lichen.

Viewing a forest needs to be three-dimensional, so we also paused to look up into the tree canopy. In the Bishop pine section of the forest, the upper pine branches were draped with strings of lichen, giving the old trees a bearded appearance. As we craned our heads upwards, two curious ravens sailed over the treetops, cawing.

I pointed out an old-growth Doug fir tree that rose high into the sky. It probably provided a nesting home for the elusive red tree vole, a small, nocturnal rodent that dines almost exclusively on its needles. I once saw one scamper across a dirt path and into the safe arms of a fir tree.

In the two hours we spent wandering and looking, fog drifted in from the coast a couple of miles away, then receded. The air and the elements are a vital part of this landscape, with the fog providing moisture for the redwood trees to survive.

As we made our way deeper into the forest looking for some elusive plants, the path petered out and we pulled branches aside or ducked under them. The piney scent of a crushed fir branch tickled my nose. Someone commented about the springy thickness of the redwood duff, like walking on a cushion. Nearby, we could hear the throaty croak of a frog in a hidden wet hole.

We stopped at two nine-foot wide old-growth redwood stumps taller than any of us, and a couple of women paused to take photographs in front of the aged stumps. Tiny heart-shaped redwood violet plants carpeted the ground in front.

With 96% of the old-growth redwoods cut down in the last 150 years, these stumps are the only local remains of a once-thriving forest of giant trees unseen anywhere else on Earth. Fairy rings of younger redwoods now grow around some of these stumps, like disciples honoring the fallen mother tree.

There is a sorrow felt in our generation over the loss of stately redwood trees as old as 2000 years, with trunks as wide as a room. It feels like an unjust theft by previous generations. It crosses my mind that we are doing that to future generations—using up natural resources faster than nature can recover them.

We walked on towards the eastern side of the property where the redwoods are taller, perhaps because their long roots sip from the stream nearby. The light is dimmer here, and deep shadows create a feeling of dark mystery—a sense of watchful waiting. I noticed a cloud cover had moved in, and people were zipping up jackets against the cooling temperatures.

When we first entered into this new area, the birds were silent. Our voices naturally dropped in volume to match the quiet of the place. As we paced slowly, talking quietly, the small birds gradually started peeping again. We passed the test of making the birds feel safe. One woman wandered off to take photos and climb onto an old tree stump.

A stream bank nearby is covered with hundreds of western sword ferns. It feels like a prehistoric setting since both redwoods and ferns have been on Earth for hundreds of millions of years. This timeless scene might have looked similar 150 million years ago, except that the old-growth trees would have reached another 250 feet into the sky—as tall as today’s thirty-story skyscrapers.

Despite the old-growth tree losses, I still feel grateful that we have the remains of these forests. I remind myself they could grow tall again, even if it takes fifteen or more human generations. The protective actions we take today will reverberate for hundreds of years to come. That’s how we leave our small human legacy.

These redwood forests— and all forests— are treasured spots to visit and learn from. They rejuvenate us when our human world seems too busy or noisily fractured. They remind us that nature has its own tempo and intelligent life force. A forest is a vibrant and creative community of hundreds of species living together.

The wild has a spontaneous rightness that arises from itself and happens of itself, an unfolding perfection and continuing completeness that is powered from within.

Canadian Zen author Ray Grigg

Maybe forests help anchor us to Earth at a time when billionaires propose establishing colonies on Mars rather than taking care of our home planet. These forests whisper, “You were created to live here.”

As our group walked back to the cars, a relaxed conversation flowed. The experience of being immersed in the woods loosened the boundaries between self and others, promoting a sense of peacefulness and group cohesion.

As my visitors climbed into their cars and slowly drove away, I lingered for a few more minutes to savor the hush and feel the cooler shift in the breeze. Then, suddenly, the raindrops started falling, and I had to laugh. It held off just until our forest tour was complete—giving me a moment for gratitude.

We need forests of all kinds more than ever now. They help us remove CO2 from the air and cool the earth, but are more than just climate allies.

They show us how to live in the world with a communal spirit, sharing and recycling resources. They bring us peace and the understanding that nature should be allowed to live at its own rhythm. Forests help ground us to the pace of Earth Time, something that should never be forgotten.🌲🌲

Robin Applegarth

Deforestation is a growing threat, particularly with tropical forests. But North American forests are also under attack.

15 billion trees are cut down every year. Apart from destroying ecosystems and triggering biodiversity loss, deforestation accelerates global warming…

To put things into perspective, we are losing forests at a rate equivalent to 27 soccer fields per minute.

10 Shocking Statistics About Deforestation, by Martha Igini at Earth.org

What can we do to stop forest losses? Work with your local politicians, land trusts, and environmental non-profits to advocate for more preservation of forested areas for recreation, climate-mitigation, and to preserve biodiversity for forest-dependent species. It takes a village to protect a local forest. 💚

P.S. If you’re local to the redwood coast area and want to get on my list for a future tour, please let me know by responding to this email. You can also reach out at MotherE@substack.com

I like to hear from readers!

You can make a public comment at the button above, or respond to your subscriber email to reach me privately. You can follow me on Mastodon social media: @RobinApple@mastodon.social

If you liked this article, please hit the heart ❤️button at the bottom or top as it helps more people find it on Substack. Thank you to readers who have referred the Mother E newsletter to friends and shared on social media!

Not subscribed yet? Mother E is a free newsletter about our connections to other species in a climate-changing world. Sign up below to have it delivered to your email box on the first Sunday of each month.

I enjoyed reading this post. I visited California when i was about nine and I still remember the awe I felt walking among the redwoods, amazing trees. Oddly there are two redwoods in a small cemetery here in Edinburgh! Scotland of course has its own forests, including temperate rainforests that are a declining habitat, sadly.

I live in Gualala and am wondering where you hiked.