A Close Link— Food and Planetary Health

New crops for a warmer, drier planet/ How eating more rainbow foods helps biodiversity/ Indigenous cultural links to maize

You’re at Mother E, a free newsletter about our connections to nature and other species in a climate-changing world. If you missed the last edition, it’s here: The Changing Sounds on Earth

If this newsletter gets shortened by an email program or the images don’t show, you can read it on the website here. To get Mother E coming to your email box every other Sunday, signup below.

I’m taking some time off in August from writing longer essays so this Mother E issue will include shorter pieces. You’ll see more links of things I’ve read or that have inspired me. This week, the common thread is food and the species we raise to feed us.

Enjoy!

Robin Applegarth

Five unusual foods you might be eating soon

The climax of summer foods is here and farmers’ markets are bountiful. What’s new on the food horizon? Maybe it’s the search for new plant foods that can survive in a hotter and drier world.

Mother E is about our connections to other species in a climate-changing world. There is no closer or more intimate connection than that between our bodies and the food we consume.

This food, whether it comes from plant species or animal sources, is the intermediary that brings sunlight, Earth’s minerals and rainfall into our bodies in a format we can use for energy and growth.

Plants produce an amazing variety of edible fruits, leaves, roots, and grains. A slippery mango is very different from a stalk of dry oats or a chunky beet root, yet they share the same plant processes: gather sunlight through photosynthesis, drink rainfall or irrigation, and transmute Earth’s minerals into plant growth.

Throughout history, humans have cultivated 6000 different plant species according to the recent Guardian article below. Many of those species are lost to extinction or obscurity but a few are gaining new importance.

Diet for a Hotter Climate: five plants that could feed the world.

Today, over half of the world’s calories are provided by only three crops: wheat, corn, and rice. This limited trio of important grains is being affected by the climate crisis and drought, leaving a vulnerability for our food sources.

Farmers are now faced with finding crops that can survive higher temperatures, erratic weather, and drought conditions. Enter five hardy and nutritious plants: amaranth, fornio, cowpeas, taro, and kernza. If you’re curious about what they look and taste like, skim the Guardian article here. If you’ve eaten all five of these plants, let me know how you liked them. :) We’ll be seeing more of them in the decade to come.

Altering leaf structure to boost crops

Human ingenuity is impressive, but it’s even more successful when combined with the wisdom of plants and nature. Researchers studying leaf photosynthesis have experimented with a genetic alteration of soy leaves which could boost crop production.

The research was done over only only two crop seasons and in one location, but the findings hold some promise for boosting soy crops, which are widely consumed by domestic animals as well as people.

Researchers increased yield in soy plants by making them better at photosynthesis, the process that powers life. The findings hold promise for feeding a warming world.

NY Times—Scientists boost crop performance by engineering a better leaf

Genetically modified organisms (GMO) have been around for decades and many of us consume them regularly. Most major grains are GMO, as are many fruit and vegetable crops.

The jury may still be out on which GMO plants and foods are safe for long-term growing. We’ve learned that all plants, including large-scale mono-crops grown on thousands of acres, interact with wild insects, birds, and other plants. Some GMO foods may create unintended or unwanted interactions with other species. In the rush to produce more food, let’s not forget that nature has billions of years of experience at plant evolution for us to learn from.

Weaving indigenous corn with sacred prose

Native American maize/corn has been a cornerstone of indigenous diets for as long as tales have been told. It’s never been just about planting the corn seed in the soil, nurturing it and waiting for the harvest, though.

Corn occupies an almost mythic role, including in creation stories and ceremony. It’s been called: The Seed of Seeds, Our Daily Bread, Wife of the Sun, and Mother of All Things. Columbus tasted it and wrote in his journal the local indigenous name— mahiz or Bringer of Life, which evolved to the word maize.

Native planters have bred maize for thousands of years, using traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), improving and altering these plants in a respectful relationship between human and plant.

You can listen to or read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s poetic prose article Corn Tastes Better on the Honor System.

https://emergencemagazine.org/feature/corn-tastes-better/

Here’s a passage:

I hold in my hand four seeds in the colors of the medicine wheel: thundercloud black, solar yellow, pearly moonlight, and blood red. I hold in my hand the memory of my ancestors in the garden. The DNA in every cell carries the story of brown fingers poking these seeds into the earth, fingers just like mine, with dirt under their nails. These farmers nurtured not only food but extraordinary genetic diversity, with the capacity to adapt to changing climates and an always uncertain future. I could use some of that now. This is the fruit of sophisticated indigenous science: traditional ecological knowledge, known as TEK.

Corn Tastes Better on the Honor System, by Robin Wall Kimmerer

How does our diet affect wild animals?

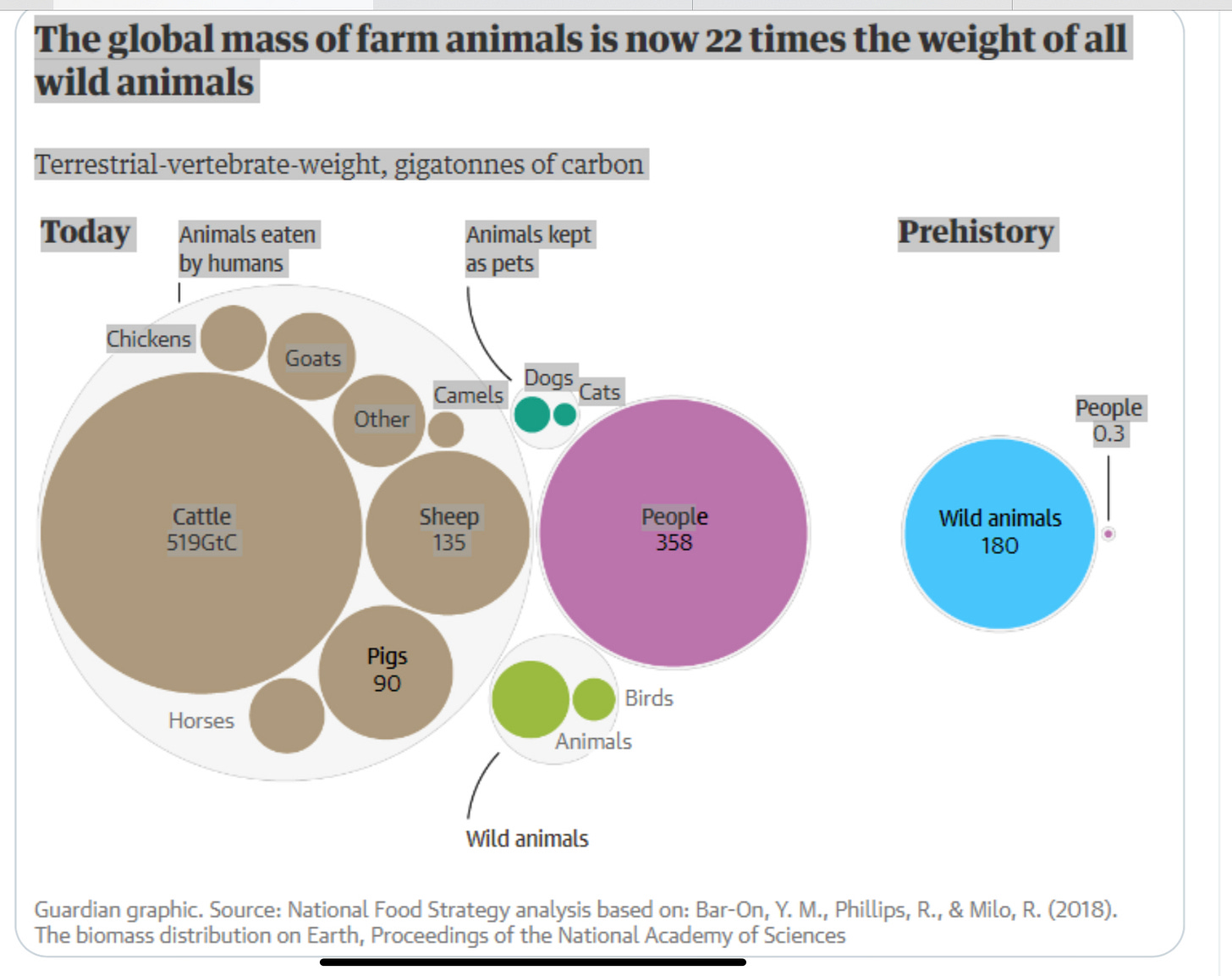

And to wrap up— how does our diet impact the wild (and wider) world? This chart shows the astonishing change human consumption of industrial farm animals has brought to the planet.

To summarize this chart, it shows terrestrial vertebrate animals by mass. On the right side is a blue circle showing wild animals in prehistoric times. On the left side is current wild animals in the lower green circles. People are the purple circle and the largest bubble of brown circles is the mass of all the animals on Earth now that are raised for human consumption— 22 times that of all wild animals today.

This level of meat eating (mostly in the Western world), is unsustainable and one reason I stopped eating beef years ago and shifted to more plant-based foods. My current challenge is lessening dairy products which come from cows.

Cattle are especially inefficient at converting plants and water to food. One pound of beef uses about 1,800 gallons of water on average, including the water used for the plants to feed it. Currently, large tracks of land are still being cleared in the Amazon to raise cattle, resulting in vital forest and biodiversity loss. Livestock are also responsible for 14.5% of greenhouse gases, according to this UC Davis study.

A diet for a sustainable planet includes much more plant-based proteins, is a more efficient way to feed people, uses less water and land, and produces fewer toxic byproducts. In short, plant-based eating has a much smaller footprint on Earth.

If we could take some of the large tracts of land being used for grazing and re-wild them, we could improve habitat for wild animals and birds and pull down more carbon from the air at the same time. If we want to protect wild species and biodiversity, we’ll need to adopt planet-friendlier eating.

There are almost 330 million people in the U.S. If one quarter of them halved their meat consumption in the next year, we could see improvements rapidly.

Changing a diet to be more Earth-friendly does not require an all-or-nothing approach. If you’re a meat eater who cares for the planet, start with a meatless Monday or cut out one type of meat from your diet. Focus on putting more colorful foods on your plate. One pediatrician who was encouraging more produce consumption told his young patients, “Eat more rainbow foods.” For inspiration on plant-friendly cooking, check out the flavorful food ideas at ACoupleCooks.com

The food question for the current decade is—how do we feed the almost 8 billion people on Earth in a way that nurtures us and regenerates the planet for ALL species?

I’m heading off to the farmer’s market today with my basket to collect rainbow-hued foods, courtesy of our local farmers. Rainbows are signs of hope and a promise of new beginnings. They also represent all-embracing inclusivity, a perfect metaphor for a diet that recognizes there are many others that share Earth with us.

Cheers!

I like to hear from readers. Food choices in today’s world are both personal and interrelated with the needs of other people and species. How do we balance those needs?

You can comment at the button above, respond to this email to reach me privately, or reach out on Twitter @RobinApplegarth.

Not subscribed yet? Mother E is a free newsletter about our connections to other species in a climate-changing world. Sign up below to have it delivered to your email box every other Sunday.